Post-Shot Expected Goals (PSxG): What is it and why does it matter?

Explaining Post-Shot Expected Goals (PSxG): Part of our series on new forms of football statistics.

Part 1 of 3 in a mini-series on modern football’s most cutting-edge statistics, by Sollie Cook.

In recent years, football clubs and fans alike have become increasingly obsessed with stats as a means of understanding player and team performance.

This fascination with numbers has led many clubs across Europe towards a data-driven approach to their recruitment and training methods in pursuit of a failsafe ‘winning formula’.

Individual performances are now routinely broken down into seemingly endless streams of numbers and graphs, outlining every aspect of the game you could possibly imagine. This enables a club or manager to understand exactly what a player’s strengths and weaknesses are.

Traditionally, raw statistics like ‘shots on target’, ‘passes completed’ and ‘saves made’ were the primary method of analysis for clubs across the world. However, these types of statistics are no longer favoured by analysts, scouts, and managers, as they are viewed as too simplistic, disregarding the context of a given game or match scenario.

They are instead being replaced by contextualised and adjusted stats such as Expected Goals (xG), which allow for fairer comparison between players, teams and even leagues.

One such metric is Post-Shot Expected Goals.

In part 1 of this mini-series on modern football stats, we look at what Post-Shot Expected Goals actually is, why it matters and what we can learn from them.

It all starts with Expected Goals (xG)

If you have ever shouted the words ‘they should have scored that’ at the TV when your club’s striker misses a sitter, you are already acquainted with the concept of Expected Goals.

In its simplest form, xG is a metric that tries to put a number on the extent to which that player ‘should have scored that opportunity.

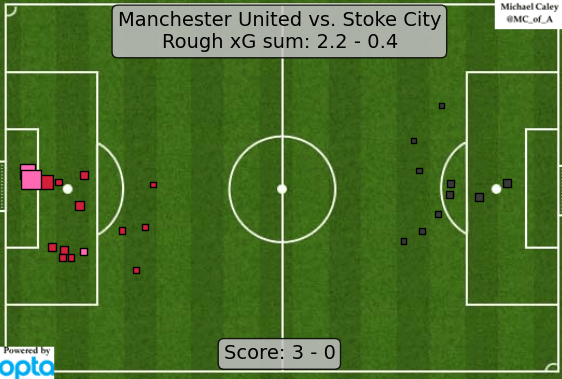

In more technical terms, Opta defines Expected Goals as ‘a measure of the quality of a shot based on variables such as assist type, shot angle, distance from goal, whether it was a headed shot and whether it was defined as a big chance’.

For example, a shot from 30 yards out at an angle will have a far lower xG than a shot taken from the penalty spot.

Adding up a player or team’s xG gives an indication of how many goals they should have scored on average, given the shots they have taken in a game.

The difference between xG and PSxG

Post-Shot xG takes this to the next level, further eliminating the impact of external game factors.

The key difference between the two is that PSxG takes into account what happens to the shot once the ball has left a player’s boot.

For example, if two shots are taken from the same location under the same set of conditions, they would have the same xG value. However, if one of these shots is a scuffed effort put straight at the keeper, whilst the other is a clean strike towards the top corner of the goal, the former would have a significantly lower PSxG value than the latter.

This is by no means a revelation, but there are simply certain areas of the goal that are more beneficial to aim shots at. Although these areas differ based on the shot location and goalkeeper positioning, the corners of the goal generally represent the best odds of finding the back of the net.

What PSxG tells us about strikers: Clinical finishing

This metric helps us measure two key player attributes. The first of these is how clinical a player is at shooting.

Because xG is only an estimate (albeit a fairly good one), players often go through spells of over or underperforming their xG. However, this output usually returns to somewhere near the expected average over longer timeframes.

As with anything, there are certain players that buck the trend, consistently over or underperforming their xG.

To find an explanation for these anomalies, we have to find a way of measuring how clinical a player is at finishing chances.

The best way of doing this is to compare a player’s PSxG with their xG. If the former exceeds the latter, it suggests that they are able to regularly produce higher quality, more accurate shots than the average player from that position. This figure is known as ‘Shooting Goals Added’, SGA for short.

Over the years, the likes of Wayne Rooney, Robin Van Persie, Harry Kane and Mohammed Salah have somewhat unsurprisingly all boasted impressive SGA records in the Premier League.

Although it is by no means a definitive measure, a high SGA statistic is usually a good indicator of a lethal finisher.

What PSxG tells us about goalkeepers: Shot stopping

The second attribute that PSxG quantifies is a goalkeeper’s proficiency at making saves.

Whilst some goalkeepers may catch the eye, pulling off save after save, this is often because they play in a team that faces a lot of shots. It may sound obvious, but the more shots a keeper faces, the more saves they are likely to make.

By the same token, goalkeepers playing behind watertight defences may boast impressive clean sheets and save percentage records, but this is likely a result of their team’s system limiting their opposition to few and low-quality chances, rather than being entirely attributable to their own individual brilliance.

It is therefore clear that relying on ‘volume-based’ stats is an insufficient method for telling how good a goalkeeper is.

Because PSxG factors in the quality of the shot taken rather than just the quality of the opportunity, a goalkeeper’s ability to make saves can be universally judged by the difference between their goals conceded and the PSxG of the chances they face. Conceding fewer goals than PSxG suggests indicates an above-average number one.

A perfect example of this is David De Gea’s remarkable 2017/18 season, during which he kept 18 clean sheets. Throughout that campaign, the Spaniard faced 39.7 goals worth of PSxG. However, he conceded only 28 goals, almost 12 less than expected.

Although playing behind a solid defence undeniably contributed to his clean sheets statistic, this deficit of almost 12 goals must be attributed to the brilliance of De Gea during that season, as PSxG faced removes such external factors from the equation.

With these factors stripped away, PSxG allows us to simply measure shot-stopping ability, which, despite the ball-playing requirements of the modern goalkeeper, surely remains the most important skill for a keeper.

For more great football content check out all of our football stories, opinions and interviews.